The 19th Century Glass at All Saints’

Introduction

Any visitor to All Saints cannot help but be impressed by the splendid stained glass windows. They are all from the workshop of Charles Eamer Kempe (1837 – 1907), probably the most famous stained glass artist of the Victorian and Edwardian eras. His style is immediately recognisable. To quote Jane Brocket in her book How to look at Stained Glass – ‘The things to look for are the faces, the peacock feathers and pearls, the jewels and ermine-trimmed robes, the lavish use of silver stain, and the maker’s mark.’ All of these, apart from the maker’s mark (a wheatsheaf) can be seen at All Saints.

The South Chancel Window

This window appears at its best when it is lit up by direct sunlight. It is a window depicting five saints in the order: male, female, male, female, male standing on pedestals in elaborate canopies. The middle three are all biblical: St Mary Magdalen, St Andrew and Saint Martha. They are surrounded by two non-biblical saints: St Nicholas and Saint Cuthbert. Notice the canopies. For the odd-numbered saints they are red above the canopy and blue below (inside the canopy), with the colours reversed for the even-numbered saints. As is the general rule they can be identified by their iconography such as what they are holding. Here however they are identified with their names, surrounded by their crowned initials. Let us look at each saint in detail.

St Nicholas

If were not told his name we might mistake him for St Christopher at first sight. The iconography however soon proves us wrong. The saint is holding a crosier and wearing a chasuble and a mitre – Nicholas (270 – 343) was bishop of Myra. The child does not have a halo and therefore cannot be Christ. Among other things, Nicholas was the patron saint of children.

St Mary Magdalene

This image is more problematic. We can tell that is Mary Magdalene because in her left hand she is holding an alabastron (a vessel containing oil for anointing). There are several references to anointing in the bible. Now when Jesus was in Bethany, in the house of Simon the leper, there came to him a woman having an alabaster box of very precious ointment, and poured it on his head as he sat at meat. (Matthew 26, 6 & 7) – also Mark 14, 3, where the ointment is described as spikenard. Mary also anoints Christ’s feet. Then took Mary a pound of spikenard, very costly, and anointed the feet of Jesus, and wiped his feet with her hair …. John 12, 3. Perhaps this last quote explains why, as in our case, she is shown with long fair hair. If you look closely at her clothing it contains ermine. This white fur with black spots was very rare and precious and indicated royalty or wealth. The fact that Mary is considered wealthy is based on Luke 8,1 & 2, where she is named among others as ministering to Jesus ‘of their substance’ ie aiding him from their resources. She also, as we have just seen had a jar of very precious ointment. But wait! What are those fierce looking beasts at her feet? I have two suggestions. Firstly it may concern a reference in Luke 8, 2 And certain women, which had been healed of evil spirits and infirmities, Mary called Magdalene, out of whom went seven devils . . . Ifyou look carefully you should be able to see seven devilish creatures. Another explanation, not dissimilar, is that as a former ‘sinful woman’, she has escaped the beasts of hell.

Finally let us turn to the writing in the book she is holding. In a fine Victorian Gothic script we read ‘Pro saliunca ascendet abies et pro urtica crescet myrtus’. This is taken from Isaiah 55,13 and means ‘Instead of the thorn shall come up the fir tree, and instead of the brier shall come up the myrtle tree ‘. This is rather enigmatic! My interpretation is that bad things being replaced by good things mirrors Mary’s life as a former ‘sinful woman’ being replaced by a follower of Jesus.

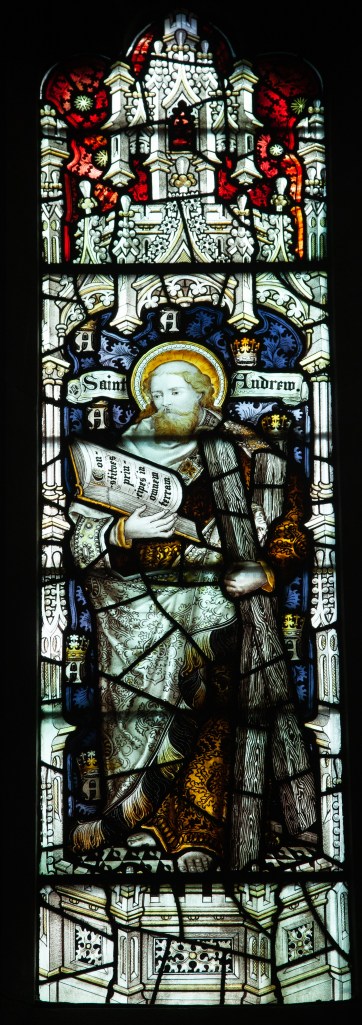

Saint Andrew

This image is slightly more straightforward.

We see the bearded, barefoot (but gloriously attired!) apostle holding the saltire (an x-shaped cross) in his left hand. This, according to a relatively late tradition, was the means of his martyrdom.

The inscription in the book he is holding is problematic, unless I am missing something. It reads ‘Constitues principes in omnem terram’. I can’t find any reference to this anywhere in the bible. The nearest is in a gradual for the feasts of SS Peter and Paul is ‘Constitues eos principes super omnem terram’, which means ‘You will set them up as princes above every land’. What we have here however baffles me! I have one suggestion. For the sake of space the artist replaced super with in. He should then have changed in omnem terram to in omni terra. All suggestions welcome!

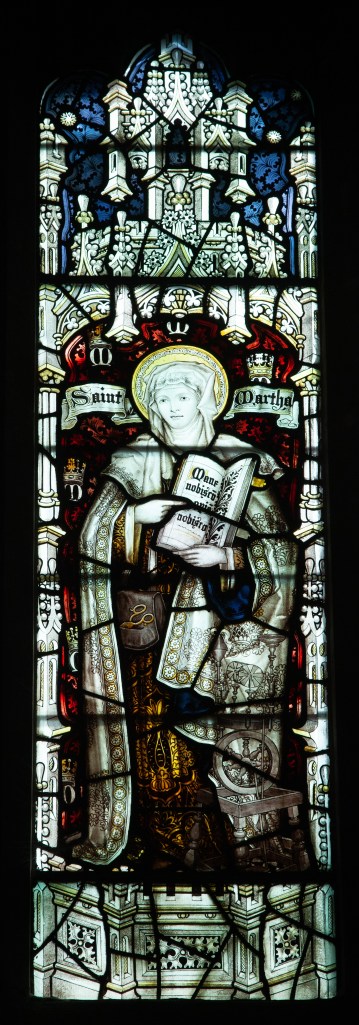

Saint Martha

Firstly why Saint Martha? I think this only works if we take Martha as being the sister of Mary Magdalene. This is a vexed question as some people see Mary of Bethany as being separate from Mary Magdalene, while others see them as one and the same. The relevant passage for the depiction of St Martha is in Luke 10, 38 – 42. ‘Now it came to pass, as they went, that he (Jesus) entered into a certain village: and a certain woman named Martha received him into her house. And she had a sister called Mary, which also sat at Jesus’ feet and heard his word. But Martha was cumbered about much serving, and came to him, and said, Lord, dost thou not care that my sister hath left me to serve alone? Bid her therefore that she help me. And Jesus answered and said unto her, Martha, Martha, thou art careful and troubled about many things: But one thing is needful: and Mary has chosen that good part, which shall not be taken away from her.’

Thus Martha is shown to be concerned with domestic tasks. That is why she is shown here with spinning-wheel and scissors and thread in her pocket.

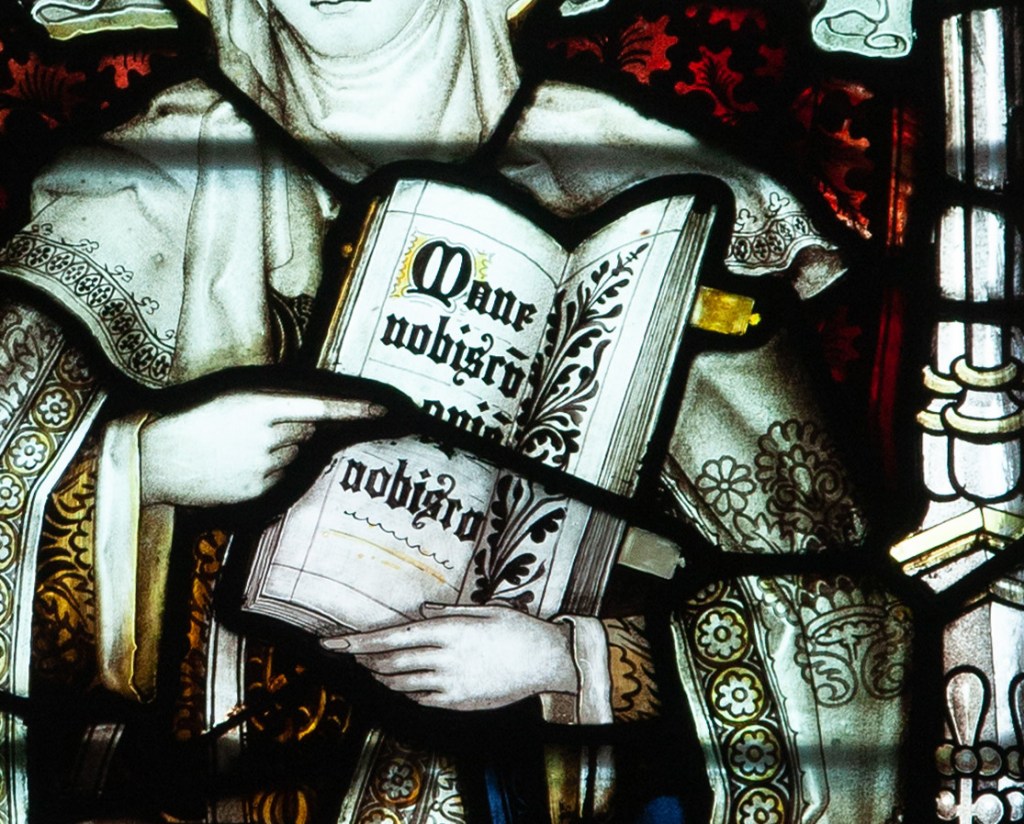

The quotation in the book to which she is pointing is also relevant. It reads ‘Mane nobiscum’ (Stay with us). This was said by the disciples to Jesus on the road to Emmaus, but is equally fitting for Martha inviting Jesus into her house.

Saint Cuthbert

Saint Cuthbert (634 – 687) was an Anglo-Saxon bishop of Lindisfarne in the Kingdom of Northumbria. He is buried in Durham cathedral. It as a bishop that he is shown here, holding a crowned head – CAPVT . S. OSWALDI means ‘The head of Saint Oswald’. St Oswald (604 – 642) was King of Northumbria from 634 to his death at the Battle of Maserfield. He promoted the spread of Christianity in Northumbria. St Cuthbert is traditionally shown holding the head of St Oswald because the head was interred with the body of St Cuthbert in Durham cathedral.

Notice the dedication of the window in the bottom right hand corner. It reads: Alice Isabel, wife of Robert Bloomfield Fenwick, fell asleep 17th January 1893 aged 48. Jesu mercy. She had died on 17th January 1893 – “loved, respected and remarkable for the gentleness and universal kindness of a simple and unostentatious life of piety and service for others.” The window – was constructed at a cost of £130!

The S. Michael Chapel East Window

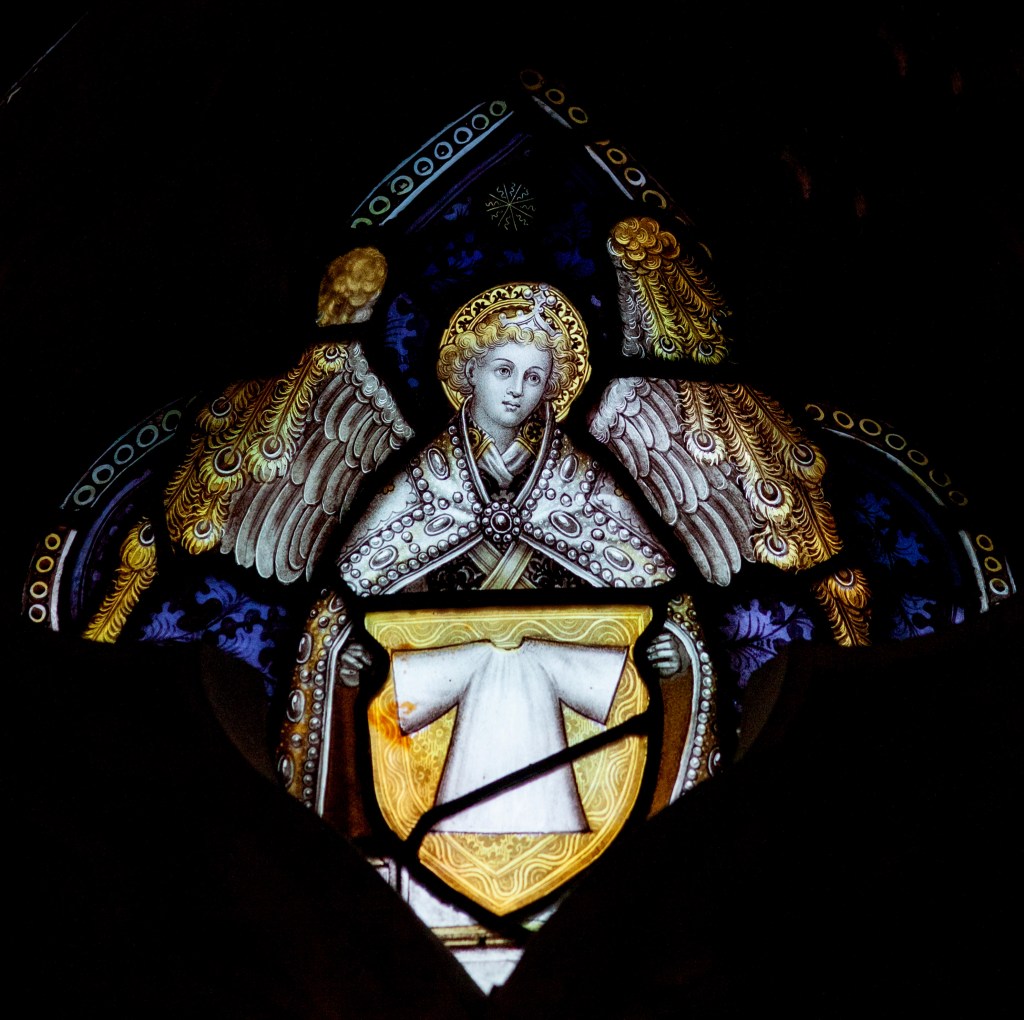

This splendid window depicts the Archangel Michael and various other angels.

In the centre at the top is the monogram IHS on a crowned shield with a sunburst. This matches a similar design on the main east window. The letters IHS spell the first three letters of the name Jesus in Greek (H is a capital ‘e’ in Greek). Beneath this are four angels playing musical instruments. They are standing on crenelated towers and looking down.

Notice the stars dotted around behind them, suggesting further that they are heavenly beings. The background colours for these angels are nicely balanced – blue, red, red, blue. The instruments they are playing are, from left to right: a tabret (tambourine), a shawm (an early reed instrument – the precursor of the modern oboe), a harp and another shawm. They call to mind a verse in Psalm 149:

‘Let them praise his Name in the dance : let them sing praises unto him with tabret and harp.’

Angels were frequently depicted with instruments in medieval stained glass windows.

Look closely at the angels’ wings and you will see that they have peacock feather designs. This is a particular feature of angels in Kempe windows. Variety is achieved by employing different colours.

On each side of these angels and on either side of the IHS monogram are lights containing acanthus leaf decoration. Acanthus leaves also appear in the background of many of the windows in the church.

Underneath these musician angels and surrounding the Archangel Michael are 8 larger angels. They are all wearing armour. Variety is again achieved in the colour of their wings, the style of their armour and what they are holding. They are all depicted in elaborately decorated canopies.

One further thing to observe are the faces. They are all typical Kempe faces – all similar, childlike and passive.

Now we come to the main focus of the window – the Archangel Michael.

Often it is difficult to distinguish St Michael from St George (made even more difficult sometimes when St Michael sports a red cross). The key thing is that, as an angel, St Michael has wings!

The scene depicted is described in Revelation:

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, and prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven. And the great dragon was cast out, that old serpent, called the Devil, and Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

Unfortunately the window is in urgent need of attention and the devil/dragon is hard to make out.

Finally the dedication in the bottom right of the window. It reads:

‘To the glory of God and in loving memory of Edward Thurston Holland, born 10th February 1836, entered into rest 27th September 1884’. (see notes below)

This is a truly remarkable window. I suggest that a few quiet moments sitting and studying it will pay huge dividends.

(Constructed by Kempe of London, and costing £200, the window was the gift of Mrs. Holland and represents S. Michael surrounded by eight angels. S. Michael was likely to have been especially dear to Mr. Holland and his wife as the couple were actively involved in the formation of the S. Michael’s Club for Friendless Girls in South Wimbledon, and sadly it was whilst on his way to inspect the new premises that Mr. Holland met his untimely death.

The Ladies’ Association for the Care of Friendless Girls (LA) was founded in 1883 under the auspices of the Church of England, at the initiative of the women’s campaigner Ellice Hopkins. The LA’s formally declared object was ‘to prevent the degradation of women and children’, in other words to prevent girls and women from falling into prostitution because of their social, economic or family or other circumstances. The LA operated as a confederation of locally run Associations, which by 1885 numbered 106.

Edward Thurston Holland was born in 1836 and had been a Chancery Barrister by profession, but throughout his life this warm-hearted and sympathetic man had demonstrated wide compassion on behalf of his poorer brethren. The news of his sudden death caused consternation amongst the congregation at All Saints’ for he was well known to all of them, and to most a personal friend. Much of his work had centred on the establishment and promotion of the South Wimbledon Church Extension Fund under whose auspices the course had been set for the building of a new church to serve this rapidly expanding area. The congregation gathered in the school for his funeral in the autumn of 1884 would have prayed diligently that his work might continue.

He was also one of the founders of the Wimbledon Cottage Hospital, that had opened in 1870, and its first Honorary Secretary and Treasurer (Thurston Road is named after him).

By 1938 the Hospital had 74 beds – 18 for males, 26 for females and 18 for children, and 12 private rooms. At this time the cost of an in-patient per week was £3 11s 1d (£3.55), compared to £3 5s 7d (£3.20) in 1937. A new X-ray machine was installed and an appeal was launched to raise funds to modernise and extend the Massage and Electrical Treatment Departments. It was planned also to build a new female ward with 19 beds and to provide 10 more private patients rooms, as well as extending the Nurses’ Home to provide new accommodation for domestic staff.

During WW2 the Hospital became part of the Emergency Medical Scheme (EMS), with 30 extra casualty beds. By 1945 it had 93 beds, including the EMS beds (but these were reduced to 15, then 10, in 1946). The cost of an in-patient had risen to £9 1s 9d (£9.08) per week, which escalated to £12 15s 6d (£12.77) in 1947. In 1948 it joined the NHS, with 84 beds, as the Wimbledon Hospital, under the control of the South West Metropolitan Regional Health Board. It was decided to close the Hospital in October 1981 and its doors finally closed in 1983. Thereafter services moved to the Springfield Hospital.

Edward was married to Marianne Gaskell (1834 – 1920) in 1866. She was the eldest surviving daughter of Elizabeth Gaskell the English novelist, biographer, and short story writer.)

The East Window

If you stand by the font and look up the main aisle towards the high altar you will get a tantalising glimpse of the east window, largely obscured by the rood screen, its reds, greens and yellows shining like jewels. It is only when you enter the chancel that you can appreciate it in its full splendour. It is the largest of the Kempe windows in the church and bears many of his hallmarks, with attention to detail. Its design has been carefully considered. Your eyes are drawn to the central figure of Christ, flanked by Mary his mother and John the Baptist. At a lower level the great apostles St Peter and St Paul and flanking them the ‘English’ saints, St Augustine (the first Archbishop of Canterbury) and St Alban (the first English martyr). All these figures are set in elaborately decorated canopies and are turned towards the central figure of Christ. At the top of the window can be seen a crowned shield bearing the monogram of Jesus surrounded by a sunburst. On either side of this and filling the next two rows are shields bearing the ‘arma Christi’ (the weapons and objects associated with Christ’ passion)

Top Row – Thirty Pieces of Silver/Whip and Scourge/Crown of Thorns

Centre Row – The Nails/The Seamless Garment/The Dice

Bottom Row – Hyssop Stick & Spear/The Ladder

The shields are held by angels, with peacock feather wings.

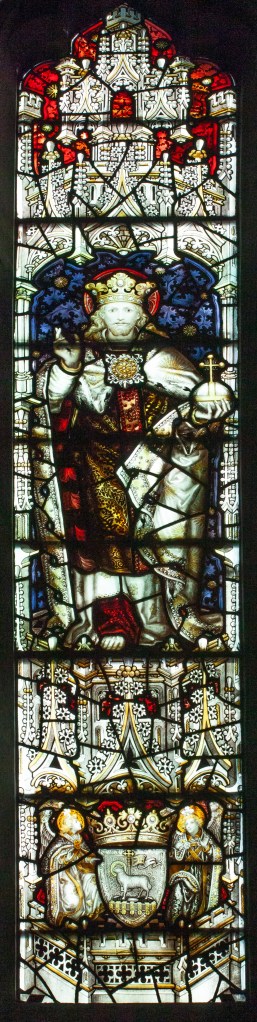

The central figure is Christ the King, Saviour of the World. He is crowned, with his right hand raised in blessing and his left hand holding the ‘globus crucifer’ – the orb and cross. His colourful clothing also suggests kingship.

Beneath Christ you can just about pick out two angels with a crowned shield showing the Lamb of God standing on a book with the seven seals. It is interesting to compare our Christ with that of Christ in St James, Ipplepen in Devon. It suggests the same template was used for both.

To the left of Christ the King is Mary.

The crown that Mary is wearing shows that she is ‘Mary Queen of Heaven’. Notice the deep blue of the garment underneath her cloak. Beneath her is an angel (with the typical peacock feather wings) holding a scroll bearing a scroll with the words ‘Tu es Rex gloriae Xte’. (Thou art the King of glory, O Christ) words from the Te Deum.

John the Baptist is to the right of Christ the King.

John the Baptist is depicted with his usual iconography: the camel hair coat, the thin wooden cross and the lamb with the scroll with the words ‘Ecce Agnus Dei’ (Behold the Lamb of God). Beneath him is an angel and scroll matching the one under Mary.

Now let’s look at the four saints who are depicted between the central figures of Mary, Jesus and John the Baptist.

At each end we have two ‘English’ saints: St Augustine, the first Archbishop of Canterbury (although he was born in Italy) and St Alban (the first English martyr). Next to these are the two main apostles, St Peter and Saint Paul.

First of all Saint Augustine.

He is shown as an ornately adorned figure, beardless, with a mitre. In his right hand he holds a cross and in his left hand a banner depicting the crucifixion. The caption on the cross reads INRI – ‘Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum’ which translates as ‘Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews’.

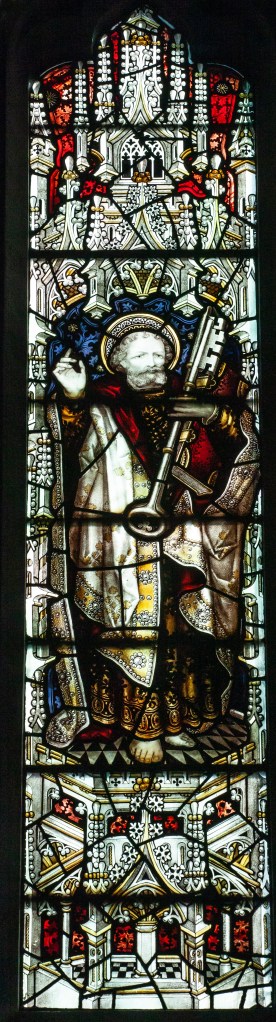

Next to him is St Peter.

He is depicted traditionally as a bearded figure with a halo and holding a huge key. This is a reference to the text: ‘I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.’ (Matthew 16: 19).

St Paul is also shown as a a bearded figure with a halo and holding a sword in his right hand and a book in his left hand. The sword represents his martyrdom and the book his writings, the epistles to the early centres of Christianity in the New Testament.

Our final Saint, Alban, is depicted as a young beardless man (his face is a typical Kempe young man face). His story goes that as a Roman soldier he sheltered a priest. He was so impressed with his faith that he embraced Christianity himself. When it came to the ears of those in authority that Alban was sheltering a priest, soldiers came to search his house. Alban exchanged clothes with the priest, was arrested, tortured and beheaded. Although he is often shown holding a cross, here he is holding a sword in his right hand – like St Paul, symbolising his martyrdom. In his left hand he holds a palm branch, the traditional symbol of martyrdom.

The dedication to Harry Pollard Ashby dates the east window to 1892. You can read more about him here.